A recent study published in the journal Nature indicates that pupil size plays a crucial role in understanding how and when the brain forms robust, long lasting memories.

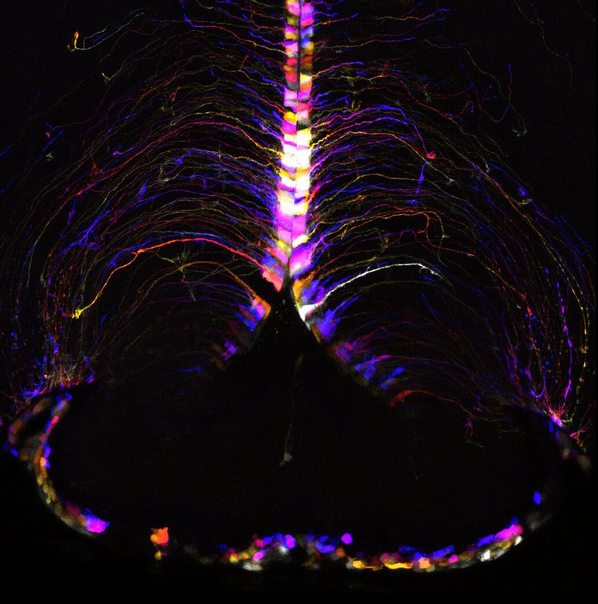

A recent study published in Nature highlights the importance of pupil size in understanding how and when the brain forms strong, long-lasting memories. Conducted by researchers at Cornell University, the study involved attaching electrodes to the brains of mice and using eye-tracking cameras to monitor their pupil size during sleep, in order to explore memory consolidation processes. The research was led by assistant professors Azahara Oliva and Antonio Fernandez-Ruiz.

The researchers trained the mice to complete tasks, such as locating water and food in a maze, and then monitored their brain activity and pupil size as they slept. As the mice learned new tasks and entered sleep, the electrodes recorded their brain activity while the camera tracked changes in pupil size, providing insight into the memory consolidation process.

During non-REM sleep, the mice’s eyes remained still, but their pupils fluctuated in size, reflecting different sleep substages and depths. These recordings revealed that the sleep patterns of the mice were more similar to human sleep stages than previously realized. The pupil fluctuations were not random; instead, they followed a precise distribution across the stages of lighter sleep.

“Non-REM sleep is when memory consolidation actually occurs, and these moments are extremely brief lasting just around 100 milliseconds, too short for humans to detect,” Oliva explained to The Independent. Despite their fleeting nature, these moments play a crucial role in how the brain processes new information.

When a mouse enters a substage of non-REM sleep, its pupil contracts, and the brain seems to replay recently learned tasks or new memories. On the other hand, when the pupil dilates, the brain appears to revisit older memories and integrate them with existing knowledge. “We propose that the brain operates on an intermediate timescale that separates new learning from old knowledge,” Oliva said in an interview with Discover Magazine. “It’s a back-and-forth between new learning and old knowledge, fluctuating slowly throughout sleep,” she added.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Sloan Foundation, the Whitehall Foundation, the Klingenstein-Simons Fellowship Program, and the Klarman Fellowships Program.